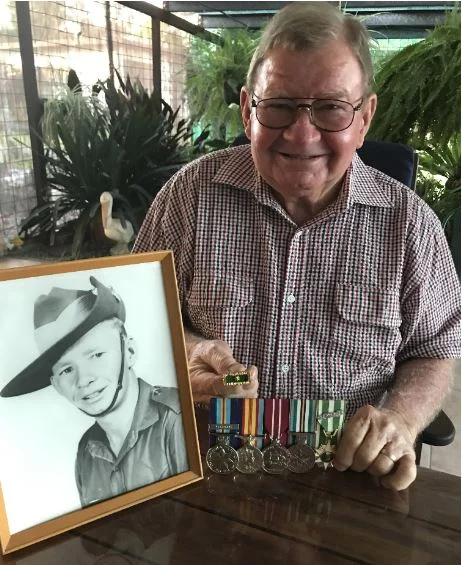

Allan Jackson – Remembering Vietnam

by Kathy Dumbleton

It was the end of 1964, and Allan Jackson was working as an apprentice carpenter in Lismore.

“The day we finished work for Christmas I went to the boss and said ‘Joe, Australia is at war, I have to go’,” Allan recalls.

Allan Jackson was just 20 in 1964, when he enlisted to fight in Vietnam.

“It was the height of the Cold War, and I believed in it, so I quit.

“I was notified of my acceptance and enlisted on the 8th of February 1965.”

At just 20, Allan was sent to Fraser’s Paddock at Enoggera Barracks in Brisbane. From here the new recruits were transported by train to Sydney and on to Kappoka, near Wagga Wagga, for three months of training.

Having a building background Allan was keen to go into engineering, but the Army had other plans and he became a medic.

Allan fondly remembers the strong sense of mateship - and a little bit of larrikinism.

“The RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major) came on one parade and introduced himself, and said he was like God.

“I said, a bit loud, I was Jesus Christ his only son, which cost me two hours punishment carrying my pack, rifle, M60 heavy machine gun and 5000 rounds of ammo!”’ Allan said.

On a 20 mile (32km) route march with full kit Allan had a severe attack of appendicitis and ended up in hospital.

Allan’s March Out Parade, to mark the end of his recruit training, was the next day and if he missed it, he’d have to repeat his whole training.

If we not parade for March Out we had to do it all again. Not for me!

“I got my clothes and walked out of hospital still groggy and unwell, but put a rifle magazine inside my trousers over my appendix and bravo, I did it!”

Allan’s first postings as an Army medic were in Victoria and New South Wales, before going to Papua New Guinea to conduct malaria surveys.

“I was forwarded to the Jungle Training Centre at Canungra in preparation for Vietnam and it was hell, particularly for people like Medics Dental Ordinance

Corps.

There was a hill that rose at about one foot for every three feet, and I didn’t want to climb it. So the Sergeant cocked the heavy machine gun and fired around me all the way up the bloody thing!”

Although Allan recounts seeing some terrible things working as a medic in the Army, the strong friendships formed were like no other.

“We had a job to do and we did our duty. I never had a mate like those I had in the Army,” Allan said.

Three and a half months in Vietnam took their toll both mentally and physically. When Allan was medevaced home his usual 84kg frame had plummeted to just 50kg.

Allan was now 22, and holding a job after he came home from war proved difficult.

Anzac Day is an event of great significance for returned serviceman Allan Jackson.

“I spent a fair bit of time in hospitals and could not keep a job. When I did get one I never mentioned Vietnam. When the boss found out, you were sacked.

“Lost three jobs like that and to this day I wish they’d had anti-discrimination laws.”

At 25 Allan was declared a total and permanently disabled solider, but his loyalty to the Army remained.

He became a foundation member of his local sub-branch of the Korea and South East Asia Forces Association, spent two years as secretary and state committee member of KSEAFA, and was secretary of the Totally and Permanently Disabled Soldiers Association social club. For 15 years he wrote a national journal for KSEAFA, was involved in Naval Cadets, and even started up a private military museum.

Anzac Day holds a special place in Allan’s heart, and he pays his own private tribute every year.

“Anzac eve I go to the lawn cemetery and lay a flower at the plaque of my schoolmates who were killed in Vietnam.

“I am proud to say I served, I gave.”

Open Arms Veterans & Families Counselling Service (formerly VVCS) provides free, confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. You can call them 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit their website.

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs provides immediate help and treatment for any veteran with a mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. To find out more or seek help for yourself or someone you know, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254, or visit the DVA website.